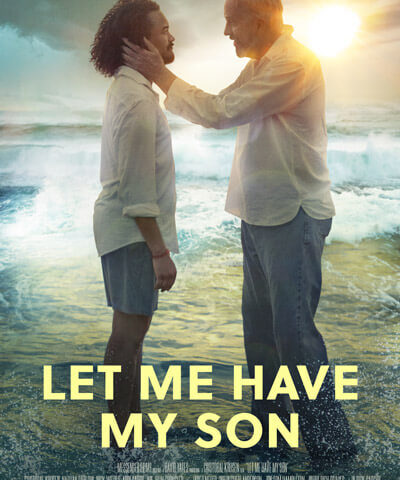

Writer/director Cristobal Krusen’s previous two films—Final Solution and Sabina K.–focus upon other people facing crises of values and faith, but his newest film—Let Me Have My Son—is a fictionalized story of his own spiritual journey that centers on his son’s descent into mental illness. He takes us on a surrealistic journey of a father visiting a mental institution where he meets many troubled souls, but cannot find his son, driving him to search all the more anxiously and ardently.

Although the writer, who also portrays the father in the film, is a devout Christian, he offers none of the easy answers to life’s “slings and arrows” offered by most faith-based films, thus lifting this one far above other films of this genre. Filled with bizarre characters who live at the mental health facility, the film at times reminded me of some of Fellini’s works. And sure enough, when I talked with the director, he quoted the Italian director in regard to his own film, “All art is autobiographical; the pearl is the oyster’s autobiography.” (More on this later.)

In a prologue an older man walks in the snow and calls out, “Benny!” Apparently, he is seeking the bearded young man who is running at some distance from him. The youth falls and crawls, crying, “I want to come home.” The older man replies, “I know, son.” There is a close-up of the father’s eyes. iI the next shot he is in bed. He rises, goes upstairs, sorts through some photos. The telephone rings. It is his daughter Genevieve (Ladonna Craelius). He tells her he wants help with the photos. They are all of Benny (Nathan Barlow). Soon he feels pain and falls to the floor. Again the telephone. He crawls toward it and faints as we hear Ginny’s voice.

Along with the front credits an ambulance siren wails. Cut to the man, lying on a gurney, wheeled through a hospital corridor to his room. Outside we see a close-up of an icicle. A doctor informs the daughter that her father has suffered a heart attack. Back home a nurse looks through the photo album as Ginny cleans out her father’s refrigerator. When Benjamin Sr. is brought home, the nurse tells him she bears the unlikely name of Holly—Holly Christmas.

During the night the telephone rings. Holly is sound asleep in a chair, so Ben picks up the phone. A nurse on the other end says, “Benny is coming home.” As Ben puts on his coat, he breaks the glass on one of the photos of his son—an ominous sign? Leaving the sleeping Holly, he goes to the garage, where he has to jump start his car due to the cold and the motor’s long inactivity. The now awake Holly rushes to the door and calls out to him as he drives off.

Arriving at the Middlemouth Security Hospital, Ben tells the man at the entranceway that he has come to pick up his son. The building is one of those huge brick Victorian buildings erected in the 19th century. Entering and inquiring about his son, he enters into a series of surreal events that make us wonder what is transpiring. There are, of course, the usual characters to be found in a mental facility—Napoleon, Cleopatra among them—and the doctors whose professionalism seems devoid of feeling. As he keeps asking where his son is, Ben is put off. Indeed, at a conference with staff members, the chief of staff Dr. Josef Bitterman tells him that he needs to sign the paperwork.

Ben joins a therapy circle where masks are used. He enters a cluttered chapel where patients quietly enter and listen to him as he picks up a guitar and sings a song, the only words of which are, sung three times over, “We Need more angels.” A stuttering patient asks, “What happened to your son,” and Ben brings us all up to date on young Ben’s sad story—of how he had lived a normal life until, after a series of incidents when he was 18 he was sent to Middlemouth Hospital; of how there had been a period when the family had lived in Mexico with Ben, where, as the father puts it, “Sometimes the best cure is love, patience, peace.” They’d hired two men to help provide care. Ben’s other children did well there, he tells the patients. For a year they lived in a lakeside cabin. (Some of the film’s most beautiful photography is of scenes in a Mexican butterfly sanctuary!)

The spell in the chapel is broken by the arrival of Dr. Bitterman, whose words, “And they all lived happily ever after?” brings everyone back to the sad present. It is he who harshly declares that Benny’s schizophrenia “is incurable.” Ben opens a note he had been given and finds “1 Corinthians 15:19-20.” He opens a Bible and reads the text. There is more. Much more. A Doctor Alejandro (Adan Rangel) seems far more sympathetic while talking with Ben, but he turns out to be a mental patient. There is Mohamed Awale (Abdi Sabrie), the janitor who seems far more concerned about finding the disappeared son than the medical staff. The father arrives so many times only to have missed his son that I found myself thinking of Artaban, the “fourth wiseman” in the film of the same name who searched for Christ all his life, always arriving a bit too late to meet and give Jesus his birth gift.

This is a far more interesting film than if Krusen had written a straightforward narrative about his son’s misfortune. We are kept in suspense and a bit perplexed, wondering if the father will ever catch up with the son, and then taken back in time to see what extremes the family took—such as moving to Mexico—to accommodate their mentally ill son. We become totally immersed in the story and often challenged to figure out what is taking place. The characters confined at Middlemouth are bizarre, and yet some of them very kind and caring. There is even a brief shot of a woman holding the prone body of Ben, reminding the viewer of a Pieta. Toward the end one patient attempts repeatedly to fit a piece into a jigsaw puzzle, which I saw as a metaphor of what I had been trying to while watching the film.

Ben Sr. keeps the faith–in the trailer you can hear him plead, “Let me have understanding… let me have peace….“Let me have strength…“Let me have patience…hope…love.”

In the film’s epilogue, we are shown a brief, moving clip of Cristóbal and his real-life son, Daniel, enjoying their visiting time together. Ben Sr. clearly is a man living in hope.

Usually, I have to search a while to find one or two Scriptures that fit with the film, but not this time. The fictional father reads in the chapel Paul’s words from 1 Corinthians. And during the second of my two telephone chats with the writer, Cris told me that his film is “a psalm of lament,” and then gave a list of Biblical psalms that include the two at the beginning of this review, and the two below:

The Lord is near to the brokenhearted and saves the crushed in spirit.

Psalm 34:18

Evening, morning and noon I cry out in distress, and he hears my voice.

Psalm 55:17

The filmmaker ended the email he sent me with this helpful observation:

“There is a reason why much of the film takes place in an other-worldly (surreal) setting. Perhaps it’s a dream Ben is having… Perhaps he is having visions and flashbacks as his life draws to a close. What is for sure is that Ben Sr. has not been able to find answers through common sense or logic. Modern medicine has not produced results. In his frustration and desperation, Ben Sr. begins looking for explanations and meaning behind his son’s mental illness in other realms.”

The release date for the film, May 24, is appropriately World Schizophrenia Day. (Didn’t know there was such a day? Me neither!). In his email Mr. Krusen observes (right after his quote from Fellini), “My son’s suffering has presented me an off the charts learning curve in empathy, compassion, hope. That is the pearl that has emerged from the pain and discomfort.” Fortunate are we in that he is now sharing his pearl of great price with the rest of us!

Read the Full Article on Visual Parables